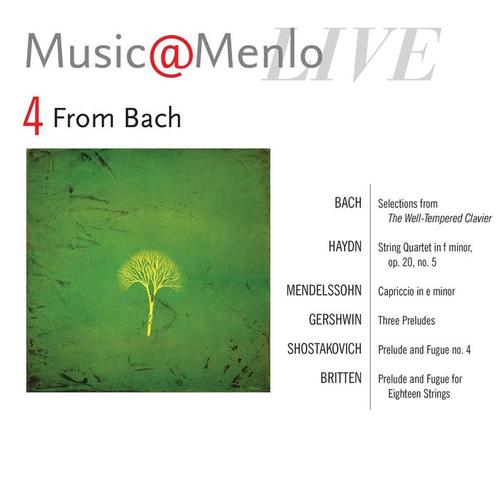

Music@menlo, From Bach, Vol. 4

Music@Menlo’s eleventh season, From Bach, celebrated the timeless work of Johann Sebastian Bach, the composer whose profound legacy has shaped Western music over the two and a half centuries since his death. Each disc of the 2013 edition of Music@Menlo LIVE captures the spirit of the season.

Disc IV delves into the tradition of the prelude and fugue. More than an academic two-part structure, the prelude and fugue, in Bach’s hands, spoke to something deeply human. The prelude is an invitation into Bach’s fantastical imagination, and the fugue is an extension of the prelude’s expression into the formal complexity of Bach’s contrapuntal mindscape. Bach’s writing captivated Haydn and, two centuries later, the likes of Gershwin, Britten, and Shostakovich.

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685–1750)

Selections from The Well-Tempered Clavier (1722)

Bach composed the first volume of The Well-Tempered Clavier in 1722. The set of twenty-four preludes and fugues, spanning all twenty-four major and minor keys, was designed, according to Bach, “for the profit and use of musical youth desirous of learning, and especially for the pastime of those already skilled in this study.” By utilizing all of the major and minor keys, The Well-Tempered Clavier also set out to demonstrate how modern systems of tuning (or temperament) allowed keyboard music to be played in any key (whereas previous systems might sound pleasing in one key but out of tune in another). The preludes are fanciful and formally free; the fugues then draw the expressive character of their corresponding preludes into their labyrinthine sophistication. The particular splendor of Bach’s preludes and fugues lies largely in, first, the creation of a captivating musical world in the prelude—and then the further blossoming of that world within the rigorous contrapuntal design of the fugue that follows.

—Patrick Castillo

JOSEPH HAYDN (1732–1809)

String Quartet in f minor, op. 20, no. 5 (1772)

The Opus 20 quartets, a set of six quartets published in 1774, reflect Haydn’s growing interest in composing in what became known as “the learned style”—serious and intellectually stimulating music, characterized by sophisticated technique and part writing that asserted the individuality of all four voices—rather than the galant style, which was less serious entertainment music, generally featuring a light, attractive melody above simple harmonies and homophonic textures. The Fifth Quartet of the Opus 20 set, in f minor, departs immediately from the galant style in its opening measures. The first theme, intoned by the violin, is stern and introspective. But as the music warms from f minor to A-flat major and the first violin shows a sunnier side of the theme, the accompaniment in the lower strings becomes more involved—as if we can hear each instrument breaking free of the old style and establishing its identity within the ensemble. Firmly in the major key, Haydn integrates all four instruments to introduce the second theme. At the arrival of the recapitulation (which, typically, would begin with a near-verbatim account of the exposition), Haydn enhances the main theme with new dialog between the first and second violin. The second movement minuet bears little of the aristocratic grace typically associated with that dance form. Instead, the severity of the first movement’s main theme is carried over and prevails over the minuet’s elegant triple meter. The contrasting trio section offers the listener some respite from the gravity of the minuet, spinning a new tune in F major. The second movement ends with a return to the f minor minuet, but the slow movement that follows revisits the key of F major with a gently rocking lullaby. The finale is a fugue on two distinct subjects: the first, presented initially by the second violin, is a disjunct melody of half notes and whole notes; against it, the second subject is a more lithe melody, played first by the viola. All four instruments quickly get involved. In its mastery of a hallowed Bachian technique, the fugue points the way forward for an immensely rich quartet literature to come over subsequent generations.

—Patrick Castillo

FELIX MENDELSSOHN (1809–1847)

Capriccio in e minor, op. 81, no. 3 (1843)

Mendelssohn’s Opus 81 comprises four short works for string quartet, composed at different times of his life but assembled and published posthumously; they were assigned the opus number 81 to follow Mendelssohn’s last string quartet, the f minor, op. 80. The third work of the Opus 81 set, the Capriccio in e minor, betrays the deep influence of Bach on Mendelssohn’s compositional style throughout his life. The capriccio, composed in 1843, follows the model of Bach’s preludes and fugues. It comprises two distinct sections, beginning with a doleful Andante con moto. This music—consisting of just twenty-eight bars—serves as a short prelude to the main body of the capriccio. It arrives at a brief, cadenza-like passage in the first violin. With this phrase hanging in the air like an open question, the impassioned Allegro fugato begins.

—Patrick Castillo

DMITRY SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–1975)

Prelude and Fugue no. 4 in e minor, op. 87 (1951)

In 1950, Shostakovich visited Leipzig, the city where Bach lived and worked for the last three decades of his life. Attending a Bach competition, Shostakovich heard the Russian pianist Tatiana Nikolaeva perform Bach’s The Well-Tempered Clavier. Inspired by what he heard, he set out soon thereafter to compose his own series of Twenty-Four Preludes and Fugues for Piano in each of the major and minor keys. He completed the set, published as his Opus 87, between October 1950 and February 1951. The Opus 87 Preludes and Fugues invite obvious comparison to Bach. But despite the homage to the Baroque master, Shostakovich’s preludes and fugues strongly demonstrate his own, modern voice. Like Bach’s The Well-Tempered Clavier, they exemplify impeccable counterpoint and fugal technique and demonstrate a deep understanding of writing for the piano. But in their expressive character, the Opus 87 Preludes and Fugues are unmistakably Shostakovich.

—Patrick Castillo

GEORGE GERSHWIN (1898–1937)

Three Preludes for Violin and Piano (transcribed by Heifetz) (1923–1926)

By the time George Gershwin had published his Three Preludes for Piano in 1926, he had already risen from a young piano-roll maker to a mature international composer—two years prior, he had debuted his wildly successful Rhapsody in Blue. His authentic “American” style of combining aspects of blues, folk, jazz, and classical music in his writing elevated him to one of the greatest cross-genre composers in American history. The short compositions for piano captivated the great violinist Jascha Heifetz, who transcribed them for violin and piano. The first prelude, Allegro ben ritmato e deciso, carries a strong baião rhythm (a signature syncopated rhythm from Bahia, Brazil) in the piano, while the violin soars playfully with a light, jazzy melody. Incorporating an assortment of “blue notes,” Gershwin makes hefty use of the blues chromatic scales. Beginning and ending with a pensive melancholy, the Andante con moto e poco rubato creates a lullaby-like reprieve before the brilliant Allegro ben ritmato e deciso brings in a call-and-response duet between the two instruments.

—Andrew Goldstein

BENJAMIN BRITTEN (1913–1976)

Prelude and Fugue for Eighteen Strings, op. 29 (1943)

The Prelude and Fugue for Eighteen Strings superimposes onto Bach’s tradition English composer Benjamin Britten’s own uniquely modern perspective. The ensemble comprises eighteen distinct string parts: ten violins, three violas, three cellos, and two double basses. The prelude begins with an impassioned exchange of loud pizzicato and declamatory chords, anchored by octaves in the double basses. Two distinct melodies emerge: one, presented in quiet solidarity by seventeen of the players, serves as a backdrop to a plaintive violin solo. At the close of the prelude, the music works its way back to the declamatory chords of the opening, now voiced in an expectant pianissimo. The sprightly fugue subject is presented in succession by each of the eighteen instruments, beginning with the second bass, then the first, followed by the cellos and violas, one after the other, up to the first violin, steadily building a massive orchestral sonority. The fugue traverses various episodes of different characters. In one such episode, the inner strings—second violins and violas—sing a long, sustained melody, while the first violins dance around fragments of the fugal subject. That music’s sweeping lyricism soon yields to a more puckish section, marked by loud pizzicato and fragments of the subject jumpily tossed back and forth throughout the ensemble. Britten’s management of eighteen individual voices is particularly impressive with the stretto near the end of the fugue: he staggers overlapping entrances of the subject, again in each voice from the second bass up to the first violin, as he builds towards the music’s intoxicating climax. A coda to the fugue turns dour; the plaintive violin solo from the prelude returns, leading to a reprise of the prelude’s opening chords. But the ebullience of the fugue has the last word.

—Patrick Castillo

About Music@Menlo

Music@Menlo is an internationally acclaimed three-week summer festival and

institute that combines world-class chamber music performances, extensive audience engagement with artists, intensive training for preprofessional musicians, and efforts to enhance and broaden the chamber music community of the San Francisco Bay Area. An immersive and engaging experience centered around a distinctive array of programming, Music@Menlo enriches its core concert programs with numerous opportunities for in-depth learning to intensify audiences’ enjoyment and understanding of the music and provide meaningful ways for aficionados and newcomers of all ages to explore classical chamber music.